The content of this newsletter

Introduction

Need to know

SAI Audit Considerations to the Impact of COVID 19 on the Extractive industries Sector

Annual WGEI Steering Committee Meeting 17th September 2020

Training Courses

Online course: how to audit government’s performance to manage oil and gas contracts

Joint WGEI and AFROSAI-E Course on how to audit government’s management of the Production Sharing Agreements

Introduction

Welcome to the seventeenth edition of the WGEI newsletter! In this edition of the newsletter, you can read about SAI Audit Considerations to the Impact of COVID 19 on the Extractive industries Sector, Annual WGEI Steering Committee Meeting 17th September 2020, Online course: how to audit government’s performance to manage oil and gas contracts, Joint WGEI and AFROSAI-E Course on how to audit government’s management of the Production Sharing Agreements.

Have a nice read!

Need to know

SAI Audit Considerations to the Impact of COVID 19 on the Extractive industries Sectors (By Edmond B. Shoko, AFROSAI-E)

Introduction

Through the literal works and publications of its various working groups and regional secretariats, the INTOSAI community has always been aware that disaster often strikes unannounced with insurmountably disruptive effects. With each disaster strike be it natural or manmade, the role of the Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) in the efforts of humankind to restore a semblance of order during these times has proven invaluable. The COVID19 pandemic is one such global disaster which has truly put to the test the disaster preparedness status of both the governments of the world and the private sector business in the extractive industries sector.

The extractive industries sector has always been regarded as a high contributor to government revenue and economic growth for many countries. It is an area where transparency and accountability are of paramount importance. Through the performance of various audits,the SAI is seen as a beacon of transparency and accountability of the proper governance of mineral resources for the benefit of current and future citizens of the country. Central to the events around COVID19 and its impact on the extractive industries sector, has been the question of the resilience of the SAIs in responding to various extractive industries stakeholder expectations in times of this pandemic. SAIs should continue to be an institution which brings in value and benefits to the citizens of its country.

It is widely accepted that the COVID19 pandemic is indeed one of a kind based on the magnitude of disruption it has brought about to the social, economic, and political construct of the way of life globally. The objective of this paper, is to establish a triage of areas within the extractive industries sector which have been affected by the COVID19 pandemic and propose audit considerations by SAIs in responding to the related audit risks.

Using doctrinal research methodology, the paper is divided into three sections. Post this introduction, the paper explores the main global events on how the extractive indutries environment reacted to the the COVID19 pandemic. From this exploration, the paper identifies the major reactions by key stakeholders in the extractive industries sector to the COVID19 pandemic and goes on to interrogate their impact on the extractive industries environment. The second section of this paper attempts to map and link the identified major reactions to a triage of key audit risk areas within the extractive industries sector. The identified triage of risk areas is then complimented by proposed SAI auditor audit considerations. The last section of the paper gives conclusions and recommendations to SAI auditors on the findings of this research.

COVID 19 and the extractive industries sector

In response to the pandemic, governments around the world adopted sweeping measures, including full lockdowns, shutting down airports, imposing travel restrictions and completely sealing their borders, to contain the virus.[1] The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the global commodity markets in a variety of ways that have challenged the extractive industries sector. Company operations have been affected through isolated outbreaks and government mandated shutdowns and the demand for many commodities remained low with a lower near-term demand on the horizon for the greater part of the year 2020.[2] Whilst the overall socio-economic impact of the pandemic on the extractive industries sector is not yet known, it can however be concluded that it will be felt for many years to come.

Several economies in the world especially in Africa are sustained by the extractive industries sector. The majority of these countries’ national budgets are dependent on mining, oil and gas exports. To date, the survival of these economies is, largely dependant on how the extractive industries are regulated during the fight against the pandemic. To this end, it is noted that special dispenseations have been given to the operations of the mining sector in several African countries despite imposed nation-wide lockdowns. For instance, South Africa allowed the reopening of mining operations under ‘Level 3’ lockdown regulations permitting mining companies to operate fully.[3] Whilst Zimbabwe and Namibia[4] allowed their mining and diamond sectors respectively to operate as essential services.[5] In the most extreme of cases, countries such as Mozambique, Angola, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo did not completely shut down mines, but some mining companies voluntarily decided to reduce their activities. This is indicative of the paramount importance of the extractive industries to the state machinery. As such SAIs have a role to play in ensuring transparency and accountability of government activities in this sector is upheld during this disaster period.

The effects of COVID19 can be classified into four major reactions by the operating environment of the extractive industries sector: (1) Unprecidented fluctuations in commodity prices, (2) Suspension of projects, lowering production and “shut-ins” decisions, (3) Investor exploration and development budget cuts, and (4) Government delays in global oil and gas licensing rounds. Below is an account of these ways and their impacts.

- Unprecidented fluctuations in commodity prices

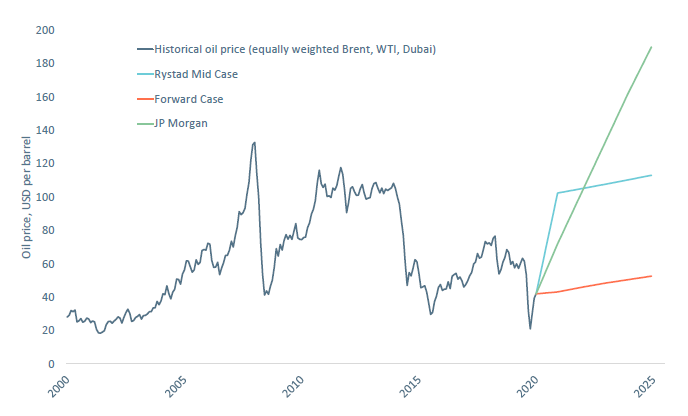

Within this environment, commodity prices have fluctuated significantly. Between April and May 2020,oil prices hit two very different first-of-its kind milestones. In April West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the U.S. oil benchmark, plunged below zero and into negative territory for the first time on record.[6] When the month of May came, oil prices shaped up to be WTI’s best month ever, going back to the contract’s inception in 1983, an astonishing turnaround month-on-month.[7] As per figure 1, JP Morgan has a point forecast of $190 in 2025 after they calculated a straight line from the then current price of $38

2. Suspension of projects,lowering production and “shut-ins” decisions

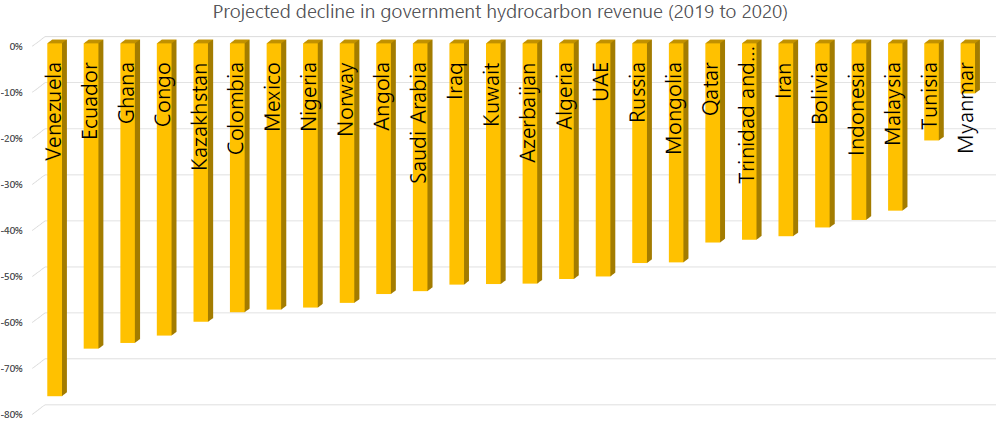

Possibly with the strategic intention to expand storage capacity and trying to market their crude oil and mineral output with the best sales and purchase agreements and financial hedging instruments possible,several mining companies suspended[8] operations[9] during the pandemic. On the other hand, well shut-ins became “the new black” as most companies, especially in the U.S. shale patch, seemed to be shutting in wells in response to what is shaping up to be the Great Glut of 2020.[10] The suspension of projects, lowering of production and “shut-ins” have a way of creating uncertainity in the extractive industries due to its technical nature. At the time of these activities, there was no evidence on the likely effects of these decisions. To date the general impact of these activities was a loss in commercial production and a decline in fiscal hydrocarbon revenues for governemnts in 2020 as depicted in Figure 2 and 3.

3. Investor exploration and development budget cuts

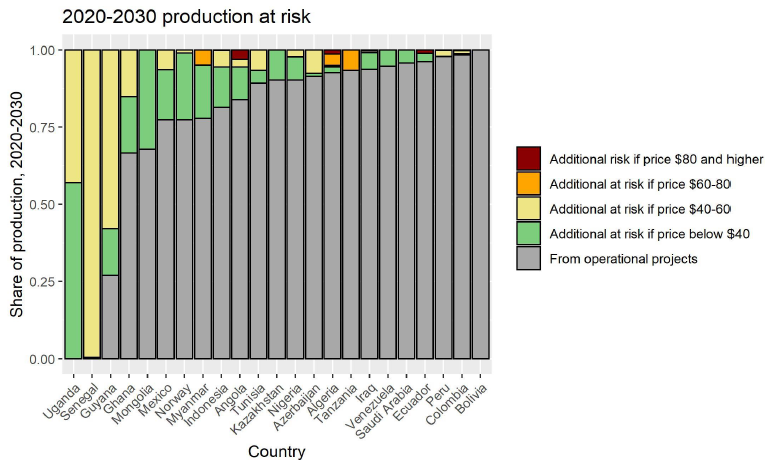

During such a volatile time, mining companies had to come up with startegies to ensure their survival in the long run. It was noted that in the wake of COVID19, mining companies reviewed their project development plans, whether they have already been launched or are still pending approval.[11] For example, extractive industries giants such as Eni and Total, the two international oil and gas majors with the largest presence in Africa, signalled 25% cuts to their investment in exploration and production projects in 2020. Such cuts work out to a €4bn reduction for the French giant and a $2bn reduction for its Italian rival.[12] It can be concluded that the impact of these cuts has contributed to an increase in the Global mean production risk for several countries, see Figure 4.

4. Government delays in global oil and gas licensing rounds

With oil and gas investors reluctant to commit an exploration budget to licensing rounds. Instinctively, this meant that licensing rounds that proceeded in the wake of the COVID19 pandemic risked receiving fewer or no bids. In response, several governments extended, delayed or temporarily suspended licensing rounds. This was an attempt to either prioritise managing the domestic impact of the virus or wait for investment conditions to improve. Bangladesh, Liberia and South Sudan were forced to announce changes to their proposed licensing rounds subsequently in 2020.[13] It is noted that the impact of these delays has been an increase in the Global mean production risk for several countries, see Figure 4.

Triage of Audit Risk Factors for SAIs to Consider

The effects of COVID19 on the extractive industries sector have been seen to be classified into four major reactions within the operating environment of this sector. These reactions in the operating environment have potentially created new audit risks and previous existing risks might have also been altered significantly for the SAI auditors. ISSAI 1315 deals with the auditor’s responsibility to identify and assess the risks of material misstatement in the financial statements, through understanding the entity and its environment, including the entity’s internal controls.[14] A preliminary review of these reactions identifies 4 key audit risk factor areas namely: (a) financial liquidity; (b) business operations; (c) Human capital and (d) the legal environment.[15]

| # | Key Risk Area & Description | SAI Auditor Considerations |

| 1 | Financial Liquidity The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on MNEs access to funding and financing with consequences for transfer pricing of intercompany financial transactions |

Due to the fundamental need to respond to liquidity crunch, auditees may have come up with forced short term and medium-term decisions to avoid haemorrhage. The auditor should consider obtaining an understanding on some of the following:

|

| 2 | Business Operations The pandemic has resulted in several disruptions to the value chain and the implications of hitting “pause” in the supply chain of the extractive industries sector. |

The supply chain disruptions have had several notable negatives “route to market” impact. These include amongst others, disrupted consumer/customer patterns, Changes to customer terms and conditions that impact the downstream value chain and Access to markets and export restrictions on ‘essential’ goods and materials. The auditor should consider:

|

| 3 | Human Capital The alignment of risk management functionality and current transfer pricing policy as a crystallization of risk due to COVID-19. |

Several areas of human capital impact have been noted for various auditees. These range from stranded or impacted executives and forced relocation of key organisational decision makers to remote working to Pressure on traditional governance models. The SAI auditors may consider the following:

|

| 4 | Legal Environment Several legal grounds to challenge or amend investor state contractual arrangements have been created by the pandemic situation. These include amongst others:

|

Several contractual clause items are vulnerable such as Pricing / payment terms; Cash flow matters; Production; Delivery; Demand / volume and Exchange rates.

Auditors need to consider:

|

Conclusion and recommendations

The objective of this paper, was to establish a triage of areas within the extractive industries sector which have been affected by the COVID19 pandemic and propose audit considerations by SAIs in responding to the related key audit risk areas. While the COVID-19 disaster has exposed several vulnerabilities of the extractive industries sector, these vulnerabilities also extend to how the SAIs need to consider their audit approaches and related risk assessment during this disaster period. From the analysis performed, the following conclusions and recommendations have been made:

- The effects of COVID19 can be classified into four major reactions by the operating environment of the extractive industries sector. To these, there are also four key risk areas which auditors need to consider in order to perform quality audits.

- SAI auditors are recommended to make considerations against the triage of four key risk areas identified as a starting point to their risk assessment and move on to strategically think of other ways in which the auditee’s responses to the four identified major crisis reactions could have affected the auditee’s audit risk profile.

- The timing of the performance and the nature of audit procedures is of essence under a state of disaster. Due to the high risk and fast paced nature of how transactions tend to occur under a disaster situation, in order to effectively offer audit services which are beneficial to the extractive industries sector, the paper proposes two timings (a) Real time audit[16] and (b) End of year audit.

- The extent of audit procedures performed is to be determined by the audit risk appetite of the SAI in relation to the risk being responded to and the level of assurance the SAI intends to provide to the users.

[1] Aljazeera “Coronavirus: Travel restrictions, border shutdowns by country” https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

[2] Deloitte 2020

[3]https://www.mining-technology.com/news/south-africa-plans-to-relax-lockdown-as-mines-re-open/

[4] http://namibianminingnews.com/diamond-producers-to-continue-operations-despite-covid-19-outbreak/

[5] https://m.fin24.com/Economy/zim-extends-lockdown-by-two-weeks-allows-mining-to-fully-resume-20200419-

[6] https://www.cnbc.com/quotes/

[7] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/25/oil-is-on-track-for-its-best-month-ever-after-rebound-but-traders-say-its-not-out-of-the-woods.html

[8] Per A. Bauer (2020) – More than 268 mine suspensions so far, some of the largest mines include: Antamina (Peru, copper-zinc), Antofagasta (Chile, copper-gold), Cigar Lake (Canada, uranium), Cobra Panama (Panama, copper-gold), Kumba (South Africa, iron ore), Panasquito (Mexico, gold-silver), Mogalakwena and Impala (South Africa, palladium-platinum).

[9] https://www.oilandgasvisionjobs.com/news-item/two-companies-suspend-production-at-some-sites-in-response-to-low-oil-price

[10] https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/The-Major-Problem-With-Shutting-Down-Oil-Wells.html

[11] https://www.theafricareport.com/27566/coronavirus-pandemic-puts-strain-30-major-african-oil-and-gas-projects/

[12] Ibid

[13] https://www.offshore-technology.com/comment/covid-19-oil-gas-licensing-rounds/

[14] ISSAI 1315 “Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment” Para 3.

[15] Ernst & Young “Transfer pricing impacts and responses” International Tax and Transaction Services global webcast. 2020.

[16] The paper defines “Realtime audit” as the “continuous” aspect of constant auditing and reporting refers to the real-time or near real-time capability for financial information to be checked and shared. Not only does it indicate that the integrity of information can be evaluated at any given point of time, it also means that the information is able to be verified constantly for errors, fraud, and inefficiencies

Annual WGEI Steering Committee Meeting 17th September 2020 (By Sheilla Ngira, Coordinator CoP WGEI, SAI Uganda)

The annual WGEI Steering Committee meeting, like a number of events this year, was held via video conference on the INTOSAI Community Portal. All 10 member SAIs of the Steering Committee: Uganda, Iraq, Fiji, United States, Ecuador, Ghana, India, South Africa, Zambia and Norway were in attendance. They were joined by SAI Indonesia and AFROSAI-E in their observer capacity.

Activity leaders reported to the committee on the progress made in implementing their activities since the inception of the new workplan (2020 – 2022) in January. Key issues included:

- Expediting finalisation of products under development,

- Adjusting the workplan and work methods to adapt to the changes caused by the COVID 19 pandemic,

- Making use of emerging technology and taking advantage of opportunities created and,

- Maintaining contact with stakeholders both internal and external.

Mr. Andrew Bauer addressed the meeting on the effect of the COVID 19 pandemic on extractive industries, specifically pointing out risks that have emerged in the industry which SAIs should look out for. Mr. Edmond Shoko further expounded on the subject by sharing the findings from AFROSAI-E’s research paper ‘SAI resilience in addressing the auditor expectation gap during disaster periods: The case of Sub-Saharan SAIs during the COVID-19 pandemic.’

All discussions at the meeting highlighted the fact that while COVID 19 has disrupted every aspect of life, work is still ongoing in the extractive industries in some form or other. As such auditors need to continue fulfilling their audit mandate whilst being mindful of the changed environment.

For details of reports and presentations at the meeting visit the WGEI website and webpage.

Training Courses

Online course: how to audit government’s performance to manage oil and gas contracts (By Marike Noordhoek, SAI Netherlands)

In June 2020 an online course on how to audit government’s performance to manage oil and gas contracts was launched on AFROSAI-E’s Learning Platform (ALP). Auditors from SAIs who want to enlarge or test their knowledge in this field can use this course for free, at any convenient time. The course is available in Arabic, French and English.

The online course developed by the Netherlands Court of Audit (NCA) builds on the insights from a regional cooperation project (2018-2020) including the Supreme Audit Institutions of Kenya (OAG), Mozambique (TA) and Tanzania (NAOT) with AFROSAI-E as a partner. The regional cooperation project was funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The purpose of the regional cooperation project was to further improve the quality of performance auditing in the field of the petroleum sector (gas and oil) and to stimulate further capacity building and knowledge distribution. The NCA supported the audit teams of the three partner SAIs in conducting performance audits in the oil and gas sector. The support included the facilitation of two regional workshops, individual country visits and distance guidance. The experience and insights from this regional project were captured in this online course as case material. The project team was supported by an industry expert throughout the project.

The online course is specifically targeted towards SAI auditors from countries (worldwide) exploring and producing oil and gas. The contracts between the government and the oil company are often called Production Sharing Contracts (PSC). Sometimes a PSC is called a PSA (Production Sharing Agreement) or Exploration and Production Sharing Contract. These are all terms for the same type of document. The information this course provides is especially useful for SAI auditors in countries using a PSC. The online course consists of four modules of about 15 minutes each. The four modules are:

- Auditing government’s contract management to protect public interest

To understand the common structure of production sharing contracts to manage the petroleum sector.

- The role of SAIs and system based performance audits in the petroleum sector

To explain the purpose and key characteristics of the various approaches to performance auditing.

- Understand fiscal terms and the importance of controlling petroleum costs

To understand why and how to move beyond compliance auditing in the petroleum sector.

- Planning a system based performance audit on government contract management

To understand different steps in a system-based performance audit in the petroleum sector.

To access the online course go to https://afrosai-e.org.za/ and click on the e-learning tab (top right). Click on register and complete the profile information. You will receive an email confirming access within 24 hours. With your confirmed username and password you can log in on the e-learning site. You can now enroll for the online course and start learning.

Queries regarding access to ALP, can be sent to Ms. Marlise Finaughty (AFROSAI-E) on the following email address: [email protected]

Did you use this online course? Feel free to give your comments and experiences on the usefulness of this product by sending an e-mail to Ms. Marike Noordhoek (NCA) on the following email address: [email protected]

Joint WGEI and AFROSAI-E Course on how to audit government’s management of the Production Sharing Agreements (By Trygve Christiansen, SAI Norwary)

Governments can choose various taxation methods when they establish their fiscal regime and decide on how to maximise government revenue from the petroleum sector. However, governments need to find a perfect balance between the need to maximise revenue and to bear an acceptable amount of risk. For many countries production sharing agreements (PSAs), also called production sharing contracts (PSCs) or exploration and production sharing agreements (EPSAs) represent the best option. For Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) auditing the management of the countries’ petroleum sector, the PSAs represent a vital source of both information and audit criteria. It is essential for SAIs to understand the setup, the legal implications, the fiscal elements and other requirements of the petroleum sector included in the PSAs. As a small contribution to this learning, AFROSAI-E and WGEI jointly arranged a one-week course in Pretoria 3-7 February 2020 for interested SAIs.

Facilitators from Indonesia, Uganda, South Africa and Norway delivered WGEI’s first ever course on how to audit government’s management of the PSAs. The combined expertise and experience from the facilitator team laid the ground for a fruitful week that stimulated learning. Participants came from among others Botswana, Egypt, Kenya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Oman, Rwanda, South Africa, South Sudan and Zambia. These countries are in different stages when it comes to implementing PSAs, but their country experiences gave important contributions to the course. Their level of preparedness, both the country and the SAI, varied.

The course covered the following topics:

- Understanding PSAs and how they relate to other legal instruments in a country

- Rights and obligations of the signatories to the PSA

- Taxes and other fiscal elements of the PSA

- Accounting, audits and financial procedures

- Upstream and midstream operations

- Local content and other requirements

- Confidentiality and disagreement

- Country examples: Indonesia and Uganda

- Identification of risks and audit topics

These different sessions generated a lot of interesting discussions and dilemmas. One of the key challenges facing SAIs is lack of mandate and/or lack of political will to allow SAIs to carry out their mandate. This challenge was experienced by some of the participants, and in extreme cases SAIs are not granted access to the PSAs at all. The facilitator team’s message was unambiguous: SAIs have full rights to access the PSAs and to audit their implementation. If this is not the case, it is a clear and serious infringement on SAIs’ ability to carry out their mandate.

There were also lively discussions on how far SAIs should go in auditing the implementation of PSAs. In some countries the capacity and competence of government is too low, especially in the area of revenue collection and ability to curb tax avoidance. In these cases it may be tempting, and sometimes necessary, for the SAI to carry out audits as a first line of control against the international petroleum companies. The question on where to draw the line on how far the SAI should go was debated intensively. Everyone eventually agreed that the SAI should be aware of the potential risk that the SAI may end up auditing its own recommendations and decisions. Ideally, a SAI should restrict itself to auditing how the government manages its role as regulator, tax collector, shareholder etc.

At the end of the course, all participants performed an overall risk assessment on their own petroleum sector and identified areas within the management of the PSAs that would require special attention by the SAI. Finally, it was agreed by both the participants and the facilitators that the 1-week course had been fruitful. For the participants it was useful to compare their own PSAs and associated risks with those from other countries. It was also useful to get the experienced facilitators’ explanations on the implications of the different articles in the PSAs, and which parts require special follow-up by the SAI. For the facilitators it was encouraging to note the high level of competence and sector knowledge among the participants, and to have a professional dialogue on questions that do not have a clear-cut answer. Truly the course provided a platform for both knowledge and experience sharing.

Going forward, it would be useful to define more specific audits, typically compliance audits or performance audits. The next step could be to compare audit plans and compare risk assessment across countries. Although the countries may differ in their competence level, maturity of the petroleum fields and level of integrity, the PSAs are usually designed in the same way. And the behaviour of the international oil and gas companies is often the same. This allows for cross-country learning on risks that all countries that have adopted the PSA model are likely to face, and which the SAI needs to act upon.