With last December’s Paris Agreement, the world community agreed on reducing the emission of greenhouse gases severely with the aim to limit global warming. What exactly is agreed on? And even more important from the WGEI perspective: how does it affect the extractive industries?

(By Marcoen Roelofs & Jeroen Doornbos, Netherlands Court of Audit)

After many years of preparation and two weeks of negotiations, 195 countries plus the European Union adopted the Paris Agreement under the United Framework Convention on Climate Change (12 December 2015). It was largely seen as a success, compared to the modest expectations and the almost complete failure of the preceding climate conference in Copenhagen. At the same time, it is clear (and even mentioned in the text itself) that the sum of all intended measures is far below what’s needed to realise the main aim: keeping climate change well below 2 Degrees Celsius, if possible even below 1.5 degree.

Main elements of the Paris Agreement

The parties (countries and regional collaborative organisations like the European Union) that negotiated the Agreement emit more than 90% of all CO2 (and equivalents) in the world. With the Agreement, its parties promised to strive to limiting global warming at the end of this century to well below 2 degrees Celsius compared with pre-industrial levels, and to try to keep it below 1.5 degree.

Moreover, the developed countries will support developing countries with large financial contributions for mitigation, and adaptation to the climate change that takes place in spite of the mitigation. The financial flows from the developed countries should reach a value of 100 billion dollar a year by 2020, the side letter makes clear (probably public as well as private funding are meant). The Agreement is due to enter into force in 2020. In a side letter, several considerations are formulated to stimulate climate action before 2020.

The Agreement creates quite a few mechanisms to monitor progress and to develop a kind of peer pressure among the parties. To give an example: each country has to formulate how it intends to contribute to the above-mentioned aims and these “intended nationally determined contributions” will be recorded in a public registry. And each country will have to account for its results.

That there is a large gap between the aims and the sum of the intended nationally determined contributions is clearly stated in the side letter to the agreement. Filling this gap is expected to be stimulated by a new report of the International Panel on Climate Change in 2018, on scenarios limiting global warming to 1.5 degree. Afterwards a ‘facilitative dialogue’ is planned in the same year to help finding solutions. This facilitative dialogue is hoped to produce a dynamic towards significant reductions of CO2 emissions, already before the Agreement enters into force.

Under the Agreement itself, a similar process of ‘stocktaking’ will take place every five years from 2023 on: evaluating if the sum of the obtained results and the intended nationally determined contributions will be enough to realise the aim of keeping global warming well below 2 degrees; if not, revising the intended contributions.

A significant step forward…

It is said that the agreement enhances the chances of really mitigating the climate change, giving a clear orientation to governmental and EU action, and to private investments.

Beyond this consensus important differences are present, most of all concerning the urgency and needed pace of climate action. Several NGO’s and think tanks like the Dutch Environmental Agency stress how enormous and urgent the task is to keep global warming well below 2 degrees and call for much quicker action. There might be a gap between the urgency documented in all IPCC reports and the reality of politicians, not eager to defend far-reaching and in the short term possibly costly transformations.

…but what does it mean for extractive industries?

A small project team in our office is currently assessing the significance of this Agreement and the consequences for the Dutch Government and society. However, we have no reason to believe that the agreement will affect our national oil and gas production. Within a decade the Netherlands has almost depleted its major reserves of natural gas and our national oil production is not significant.

This is quite different for a lot of WGEI member countries. This becomes clear when we consider the carbon potential of global fossil fuel reserves and the concept of ‘the carbon budget’.

The carbon potential of fossil fuels…

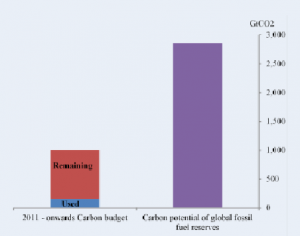

The world has still major reserves of fossil fuels. Those fossil fuels emit CO2 when burned. Carbon Tracker, a not for profit financial think tank, estimated in 2012 the carbon potential of the earth’s total reserves of fossil fuels at 2,860 GtCO2.

…is restricted by the carbon budget

However, to limit global warming to 2 degrees we can not ‘burn’ the full carbon potential, but only a part of it: the so-called carbon budget. That is the amount of CO2 that can be emitted before we reach a global warming level of 2 degrees. In 2011 this budget was estimated to be approximately 1000Gt of CO2; just one third (!) of the total carbon potential. In other words: just one third of the fossil fuel reserves could be burned. The remaining part could be burned using innovative but still immature technologies like carbon capture and storage. Alternatively those reserves should not be extracted at all. In particular, Ekins and McGlade (2014) estimate about 30% of oil reserves, half of gas reserves and around 80% of coal reserves globally would need to remain below the ground in order to keep within the 2°C goal.

And matters are urgent: end-2014 the world already consumed 15% of its carbon budget (see figure below). It is expected that the 1.5°C carbon budget will we consumed by 2021 and the 2.0°C carbon budget will be finished by 2036.

Global carbon budget vs carbon potential of global fossil fuel reserves (Bank of England, 2015)

The question for the WGEI countries

Of course, one could raise some critical remarks whether the Paris Agreement will be effective and will be enforced. However, there is a sense of urgency and it is reasonable to expect that the global community will take additional action if needed.

This raises questions for the countries that are heavily dependent on their extractive industries. Especially the countries standing on the brink of exploiting their natural reserves and currently investing heavily in their extractive industry sector, should ask themselves whether the investment is futureproof. Is it not ‘an investment in yesterday’s opportunities’ like it is an army’s nightmare to invest in the technologies of the last war? This assessment should be part of the government’s ‘business case’ before deciding to invest significantly in the extractive industry sector in order to boost economic development. Could that be something a supreme audit office should consider when auditing government’s investment plans for extractive industries?

References used for this article

-

Bank of England (2015). The impact of climate change on the UK insurance sector – A climate change adaptation report by the prudential regulation authority.

-

Carbon Tracker (2013). Unburnable carbon 2013: wasted capital and stranded assets – available at www.carbontracker.org/report/wasted-capital-and-stranded-assets/.

-

Ekins, P and McGlade, C (2014). Climate science: unburnable fossil-fuel reserves. Nature, Vol. 517, No. 7533 pages 150-152, available at http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v517/n7533/full/517150a.html.

-

United Nations (2015). Framework Convention on Climate Change – adoption of the Paris Agreement – available at www.nfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf.

-

World Energy Council (2013). World energy perspective: cost of energy technologies – available at www.worldenergy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/WEC_J1143_CostofTECHNOLOGIES_021013_WEB_Final.pdf.