Extractive Industries Auditors Toolkit

Introduction to Extractive Industries

According to the World Bank, about 3.5 billion people live in countries rich in oil, gas, or minerals and these natural resources play a dominant role in 81 countries. Africa alone is home to about 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, 10% of the world’s oil, and 8% of the world’s natural gas.Extractive industries (EI) operate at multiple scales and use a variety of methods. For mineral extraction, EI includes small-scale and Artisanal Mining as well as large-scale industrial mining operations. For oil and gas extraction, methods may include conventional oil extraction on-shore or off-shore, as well as unconventional methods, such as fracking, coal bed methane, or underground coal gasification.EI can create jobs directly and indirectly and generate significant revenue. Revenue from the oil, gas, and mining industries has tremendous potential to become a financial base for infrastructure development, social service delivery, and to lift people out of poverty. Effective governance and oversight of EI may help ensure that these benefits of resource development are realized, and that the resources are extracted in a sustainable manner.

These pages provide information for auditors who are new to EI, including links to additional resources by the World Bank, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and audit organizations such as AFROSAI-E (African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions – English).

What are Extractive Industries?

Extractive industries involve the removal of raw materials from the earth to be used by consumers. These raw materials are processed into products that are used in a wide variety of sectors, including energy, transportation, and manufacturing. The WGEI has defined the scope of its work to include oil, gas, and mining activities.

Oil and Gas: According to the International Human Resources Development Corporation (IHRDC) —an oil and gas industry training company—oil and gas provide the world’s 7 billion people with 60 percent of their daily energy needs. These resources, known as fossil fuels, originated from the decomposition of organic material compressed over millions of years. Oil and gas resources are located both onshore and offshore.

Figure: Oil and Natural Gas Formation

PIC

Mining: Minerals extracted from the ground are critical in many sectors of the world economy, including manufacturing, construction, medicine, and agriculture. For example, metals such as iron, copper, and nickel are often used in home construction, vehicles, and electronic devices. Minerals such as antimony, lithium, and potash are used in medications. Phosphate is used as a fertilizer, and fluorite is found in consumer products, such as ceramics and toothpaste.

Economic and social benefits of extractive industries can be significant.

According to IHRDC, world energy markets are continually expanding, and companies spend billions of dollars annually to maintain and increase their oil and gas production. Over 200 countries have invited companies to negotiate for the right to explore their lands or territorial waters, hoping that they will find and produce oil and gas, create local jobs, and provide billions of dollars in national revenues.

According to the World Bank, wealth on the scale experienced in some resource-rich states can generate significant positive development outcomes. Even for states with modest petroleum or mineral deposits, the outcomes from resource development and corresponding investment could be transformative.

For context, in the first decade of the 21st century, investments in mining were estimated at about US$80 billion, with much of this destined for iron ore and copper. According to the International Energy Agency, investments in fossil fuel supply reached US$450 billion in 2017.

For lower-income countries, revenues from exploiting resource wealth could exceed official aid flows substantially. In principle, such revenues could unlock the constraints of foreign exchange, savings, and public finance and support a broad range of social and physical infrastructure priorities common to developing states, according to the World Bank’s EI Source Book.

Extractive industries can have major adverse impacts and may pose challenges for governments.

Many have noted that EI development outcomes are frequently less robust and beneficial than expected.

The EI sectors can have major adverse environmental and social impacts. In the past, these issues have not always been well recognized or addressed by governments, but good practice has improved greatly since the end of the 20th century, according to the EI Source Book.

Many have noted that development outcomes in the EI sector are frequently less robust and beneficial than expected. Moreover, the outcomes can become highly damaging to the resource-rich state. Resource-rich developing states typically underperform economically relative to their peers that are not resource rich. Further, they may experience environmental degradation and have more social and political instability and violent conflict. Taken together, factors such as these have led some to describe the outcomes as the “resource curse” or the “paradox of plenty.”

Wealth on the scale experienced in some resource-rich states can generate significant positive development outcomes.

Avoiding or reducing these impacts depends on appropriate legal instruments, adequate enforcement, and fiscal structures that incentivize good behavior by investors, while recognizing the costs involved and internalizing them.

7 Steps of the EI Value Chain, Explained

According to the World Bank, the EI value chain provides a framework for the governance of the EI sector. The value chain is meant as a tool to support countries’ efforts to translate mineral and hydrocarbon wealth into sustainable development.

In its 2015 guidance, AFROSAI-E (African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions – English) expanded the World Bank’s original five step EI value chain to include the steps of establishing the legal framework and resource exploration, as shown in the figure below.

Figure: The 7 step EI Value Chain

PIC

1. Legal Framework

Legal instruments such as international treaties, national laws, regulations, and contracts provide a framework for EI. Various institutions implement the framework, and understanding the roles and responsibilities of the government and nongovernmental actors involved in EI, may help SAIs assess the government’s institutional capacity to oversee the EI sector.

Figure: Examples of Legal Instruments

PIC

Figure sources: Summarized from the World Bank ‘s EI Source Book; the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s Primer on the Legal Framework for EI; Organization For The Harmonization Of Business Law In Africa; and AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries.

Key Considerations for Oil and Gas

According to the EI Source Book, there are three distinct approaches to the design of oil and gas legislation: (1) a comprehensive, highly detailed approach; (2) individual legal contracts or agreements; and (3) a hybrid approach, as shown below.

Table: Legal Framework: Key Considerations for Oil and Gas

TABLE

Source: Summarized from the World Bank‘s EI Source Book.

Differences in development and transport costs as well as markets may necessitate specific legal provisions to encourage gas development. Examples of gas-specific provisions include:

- Allow for a longer appraisal and production period for gas and prohibit gas flaring.

- Define development incentives, pricing principles, and unconventional gas provisions.

- State priorities for domestic versus export uses and for gas re-injection into oil wells.

Key Considerations for Mining

The legal framework for mining often includes provisions covering technical, administrative, risk mitigation, and benefit distribution, according to the EI Source Book.

Figure: Legal Framework: Key Considerations for Mining

PIC

Figure source: Summarized from the World Bank’s EI Source Book.

Attributes that investors look for in mining governance are:

- Ease of access to areas for exploration;

- Clear and transparent processes, such as an open registry of mining rights;

- Tenure security that guarantees the right to develop discovered resources;

- Ability to transfer rights at no cost;

- Simple financial maintenance requirements and minimal royalty obligations;

- Ability to operate and market their output commercially; and

- Complementary provisions in tax legislation that provide the ability to dispose of foreign exchange earnings on competitive terms under contracts.

The government can include specific provisions in contracts for community development and environmental considerations—both preventative and after mining is complete—into the mining law or as negotiated conditions of mining operations.

Key guidance and further information

The following resources provide additional information on the legal, policy, and regulatory framework governing extractive industries.

![]() EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Legal Framework and Fiscal Regime (Requirement 2.1) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the licensing process.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Legal Framework and Fiscal Regime (Requirement 2.1) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the licensing process.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on the Legal Framework: Navigating the Web of Laws and Contracts Governing Extractive Industries. NRGI also provides an online tool with additional resources for members of parliament and their staff in crafting and amending EI legislation.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on the Legal Framework: Navigating the Web of Laws and Contracts Governing Extractive Industries. NRGI also provides an online tool with additional resources for members of parliament and their staff in crafting and amending EI legislation.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contractual Framework provides additional information on the governance framework for extractive industries, including challenges, policy priorities, and differences across EI sectors. Additionally, the EI Source Book has a section specific to EI governance in Central and South America.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contractual Framework provides additional information on the governance framework for extractive industries, including challenges, policy priorities, and differences across EI sectors. Additionally, the EI Source Book has a section specific to EI governance in Central and South America.

The African Mining Legislation Atlas (AMLA) is an online platform about Africa’s mining sector (mining codes, regulations, and related legislation) with interactive features to promote transparency, accessibility, and comparison of mining laws in Africa, among other objectives. AMLA is currently implemented in partnership with African Legal Support Facility of the African Development Bank and the African Union Commission, in coordination with several African universities.

The African Mining Legislation Atlas (AMLA) is an online platform about Africa’s mining sector (mining codes, regulations, and related legislation) with interactive features to promote transparency, accessibility, and comparison of mining laws in Africa, among other objectives. AMLA is currently implemented in partnership with African Legal Support Facility of the African Development Bank and the African Union Commission, in coordination with several African universities.

The Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) is a research and advocacy institution on energy and environment policy in Indonesia. IESR developed a regional framework for extractive industry governance in SE Asia.

The Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) is a research and advocacy institution on energy and environment policy in Indonesia. IESR developed a regional framework for extractive industry governance in SE Asia.

Key audit considerations

According to NRGI, a well-designed legal architecture should provide rules for how government institutions are structured, how exploration and extraction rights are allocated, the fiscal governance for sharing economic benefits, and management of impacts, among other areas. When evaluating the legal framework for EI, key audit considerations include:

Figure: Legal Framework: Key Audit Considerations

PIC

Figure sources: Summarized from the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s Primer on the Legal Framework for EI, and AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries

2. Resource Exploration

According to the EI Source Book and the Natural Resource Governance Institute, in most countries, the law or constitution establishes that the government owns subsurface resources. In turn, the government gives private companies or others the right to explore and potentially extract resources so the country can benefit from the capital generated.

Ideally, the government will consider factors, such as environmental impacts or the effects on local communities, when determining whether an area should be explored for resource. Once the government decides to open an area for resource exploration, the process followed may depend on the resource sought, the amount of geological information available, and the legal framework for EI.

For example, if geological information on the potential resource is limited or not necessarily promising, the government may decide to adopt an open-door, first-come, first-served licensing process–or engage in direct negotiations with a small number of companies.

An effective and transparent exploration contract award system is the first step toward capturing economic benefits.

However, when there is a substantial amount of geological information available and interest is high, a competitive auction–where companies submit bids to the government in a competitive process–is typically the best option to maximize the government’s benefit.

An effective and transparent exploration licensing process is the first step toward effective capture of economic benefits—and may minimize the risks of corruption. Additionally, maintaining data generated by companies’ exploration activities may help the government better understand and manage its resources, according to the EI Source Book.

The figures below summarize the various systems for awarding exploration rights and exploration methods for discovering resources.

PIC

Key considerations for oil and gas

As explained in the figure below, exploration rights for oil and gas are generally granted to a company through a contract with provisions specific to that company and the area of exploration. Additionally, these contracts typically also grant the right to develop any identified deposits. Oil and gas deposits are typically found using seismic surveys.

Figure: Exploration Rights Systems and Methods for Oil and Gas

PIC

Figure sources: Exploration rights content summarized from the EI Source Book and the Natural Resource Governance Institute, Primer on the Legal Framework for EI. Seismic survey content summarized from Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association.

Figure: Bouger Gravity Anomaly map of South India

PIC

Figure source: Rajaram, M. and Anand, S.P. 2003. Crustal Structure of South India from Aeromagnetic Data. Journal of the Virtual Explorer 12, 72-82.

Key considerations for mining

Unlike oil and gas, mining exploration rights are generally granted through licenses or permits. Additionally, exploration rights and the right to develop any mineral discoveries are granted under separate licenses. There are a variety of methods to identify minerals, depending on their location and physical properties, as shown in the figure below.

Figure: Exploration Rights Systems and Methods for Mining

PIC

Figure sources: Exploration rights content summarized from the World Bank’s EI Source Book and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s Primer on the Legal Framework for EI. Exploration methods content summarized from the New South Wales Minerals Industry Exploration Handbook, 2013 Edition.

Key Guidance and Further Information

The following resources provide additional information on the process for resource exploration.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Legal Framework and Fiscal Regime (Requirement 3.1) provides additional information on EITI standards related to exploration.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Legal Framework and Fiscal Regime (Requirement 3.1) provides additional information on EITI standards related to exploration.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on resource exploration.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on resource exploration.

AFROSAI-E: The African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions’ Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries report includes information on how to design audits during the resource exploration phase of development.

AFROSAI-E: The African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions’ Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries report includes information on how to design audits during the resource exploration phase of development.

API: The American Petroleum Institute has an explanation of how seismic surveys are used to explore for offshore oil and gas resources.

API: The American Petroleum Institute has an explanation of how seismic surveys are used to explore for offshore oil and gas resources.

APPEA: The Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association has some general information about how seismic surveys are used to explore for both onshore and offshore oil and gas resources.

APPEA: The Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association has some general information about how seismic surveys are used to explore for both onshore and offshore oil and gas resources.

Key audit considerations

From an SAI perspective, it is important to understand how the government determines who has the right to explore for resources, how potential environmental and social impacts from exploration are assessed and addressed, to what extent the government collects, stores, and uses the information generated by exploration activities, and whether the provision of exploration rights is open, fair, and transparent, among others. Below are some of the key questions that SAIs could consider when reviewing the exploration process in their country.

Figure: Resource Exploration: Key Audit Considerations

PIC

Figure sources: Summary of issues raised in the World Bank’s EI Source Book, AFROSAI-E’s Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries, and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s primer on political and economic challenges of natural resource wealth.

3. Award of Contracts and Licenses

According to the Natural Resource Governance Institute, licenses and contracts are legal documents that govern the rights and responsibilities of the government and extractive companies during resource extraction.

Licenses are typically standardized documents with generally-applicable terms across extractive projects, as established in law or regulation. In contrast, contracts are negotiated agreements that only apply to a specific location and the actors that are party to it, and may vary substantially across projects. Because a country’s ability to fully benefit from resource extraction depends upon a fair process—transparency in allocating rights and negotiating agreements is a key part of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Figure: The Process for Allocating Extraction Rights

PIC

Figure sources: Summary of steps in EITI’s License Allocation and Contract Transparency guidance notes, the World Bank’s WEI Sourcebook, and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s primer on Granting Rights to Natural Resources.

Key considerations for oil and gas

According to the EI Source Book, there are two primary methods for awarding rights to oil and gas: the non-competitive “open door” process and competitive awards.

Generally, the award method should be consistent with government policies, encourage participation, favor a merit-based selection of applicants, deter collusion, and provide some protection against pressure to distort the award process. It should also reflect the available technical, legal, and administrative capacity of the government authority responsible for awarding contracts and licenses.

Additionally, a fair and transparent award system may minimize the risks of corruption.

Table: Award Systems for Oil and Gas

PIC

Table sources: Summary of steps in the World Bank’s EI Source Book, and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s primer on Granting Rights to Natural Resources.

According to the EI Source Book, there are two primary methods for awarding rights to mining deposits: the non-competitive “free entry” process and competitive awards.Key considerations for mining

Similar to oil and gas, the award method should be consistent with government policies, encourage participation, favor a merit-based selection of applicants, deter collusion, and provide some protection against pressures to distort the award process. It should also be fair, transparent, and reflect the available technical, legal, and administrative capacity of the responsible government authority.

Unlike oil and gas, the upfront costs, risks, and value of minerals varies more across projects.

Table: Award Systems for Mining

PIC

Table sources: Summary of steps in the World Bank’s EI Source Book and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s primer on Granting Rights to Natural Resources.

The following resources provide additional information on the process for awarding contracts and licenses for resource extraction.Key guidance and further information

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s License Allocations (Guidance note 4 –Requirement 2.2) and Contract Transparency (Guidance note 7 – Requirement 2.4) guidance notes provide additional information on EITI standards related to the award process.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s License Allocations (Guidance note 4 –Requirement 2.2) and Contract Transparency (Guidance note 7 – Requirement 2.4) guidance notes provide additional information on EITI standards related to the award process.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on Granting Rights to Natural Resources. NRGI also published Twelve Red Flags: Corruption Risks in the Award of Extractive Sector Licenses and Contracts.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a primer on Granting Rights to Natural Resources. NRGI also published Twelve Red Flags: Corruption Risks in the Award of Extractive Sector Licenses and Contracts.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Award of Contracts and Licenses provides additional information on the award process for oil and gas as well as mining.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Award of Contracts and Licenses provides additional information on the award process for oil and gas as well as mining.

OpenOil: OpenOil’s mission is to create an open data framework for managing natural resources at a supranational level. It maintains an open-source data repository of over 2 million corporate filings related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. It also includes guidance documents such as Oil Contracts: How to Read and Understand Them.

OpenOil: OpenOil’s mission is to create an open data framework for managing natural resources at a supranational level. It maintains an open-source data repository of over 2 million corporate filings related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. It also includes guidance documents such as Oil Contracts: How to Read and Understand Them.

ResourceContracts.org: ResourceContracts.org is supported in part by NRGI and the World Bank. ResourceContracts.org is a repository of publicly available investment contracts for oil, gas, and mining projects. It features plain language summaries of key provisions and provides tools for searching and comparing contracts. It also includes links to several guidance documents for understanding oil, gas, and mining contracts.

ResourceContracts.org: ResourceContracts.org is supported in part by NRGI and the World Bank. ResourceContracts.org is a repository of publicly available investment contracts for oil, gas, and mining projects. It features plain language summaries of key provisions and provides tools for searching and comparing contracts. It also includes links to several guidance documents for understanding oil, gas, and mining contracts.

Key Audit Considerations

From an SAI perspective, it is important to understand how the government determines who has the right to extract resources, how the economic benefits of extraction are shared between the government and companies, how the potential environmental and social impacts from extraction are assessed, and whether the award process is open, fair, and transparent, among others. Below are some of the key questions that SAIs could consider when reviewing the award process.

Figure: Award of Contracts and Licenses: Key Audit Considerations

PIC

Figure sources: Summary of issues raised in the World Bank’s EI Source Book ; AFROSAI-E’s Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries, and the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s primer on granting exploration rights.

4. Monitoring of Operations

According to AFROSAI-E, effective monitoring practices involve clearly-defined roles and responsibilities of each party in the regulatory framework, particularly as it relates to providing or reviewing information related to production volumes, environmental impacts, and social impacts.

Monitoring of production volumes and related activities may take different forms, but usually entails regular submission of documentation, such as reports and supporting information by companies and their contractors, as well as physical inspections.

Governments may also monitor social and environmental impacts of projects. When monitoring these impacts, separation of roles and duties amongst government organizations is important. For more information on these impacts, see EI Value Chain step 7: Implementing Sustainable Policies

Figure: Aspects of Operations Monitoring

PIC

Figure source: Summary of content from AFROSAI-E’s Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries.

Figure: Monitoring Natural Gas Production

PIC

Figure source: GAO.

According to AFROSAI-E, when auditing the monitoring process, auditors should obtain documentation of monitoring activities. Auditors should not assume that oversight agencies reviewed documents or cross-checked reports to supporting documents. Auditors should identify how reviews were documented and look for notes by the reviewer about queries and corrections which may have been made.

Key considerations for oil and gas

Systems of accountability and verification are essential to monitor extraction companies’ performance, in terms of production volumes as well as monitoring environmental and social impacts.

Production Volumes

Monitoring production volumes usually entails reviewing and cross-checking documentation regularly, such as project reports and supporting information, as well as physical inspections of extraction operations and production measuring equipment accuracy.

Although some uncertainty is inherent in any measurement, it is important to avoid bias—systematic error that consistently over-or under-measures volumes. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, key controls against bias include using the appropriate meter and processing equipment for the resource; observing meter calibrations; observing sales; and verifying volume calculations accuracy.

Environmental and Social Impacts

According the EI Source Book the two common monitoring tools are environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) and environmental and social management plans (ESMPs). For ESIAs, companies analyze short- and long-term impacts of the project, and identify potential mitigation measures and monitoring methods. ESMPs are based on the ESIA, but provide more detail on how the company will manage impacts, such as its operating policies, procedures, and practices for compliance and reducing negative impacts. Governments may use these tools to monitor company performance.

Key considerations for mining

Similar to oil and gas, systems of accountability and verification—such as accounting procedures and regular independent audits—are essential to monitor mining companies’ performance, in terms of production volumes as well as minimizing environmental and social impacts, according to the EI Source Book.

Production Volumes

Monitoring production volumes or the value of material extracted usually entails auditing producer information regulatory, such as project reports and supporting data, as well as physical inspections of extraction operations and production measuring equipment to ensure its accuracy.

However, the process for measuring production volume or material value can vary greatly depending the mineral being produced, the mineral processing methods being employed, and the type of royalty being assessed. For example, some minerals such as stone, sand, and gravel—where processing is usually limited to washing and separation—are generally measured in volume or weight directly at the mine site.

In contrast, metal minerals such as copper may be sold as ore concentrate or refined for use in various applications. As a result, royalties for copper may be assessed either on the volume of ore extracted or the value of product.

Figure: The Various Production Phases in Mining

PIC

Figure source: Summarized from the World Bank’s EI Source Book

Measuring volumes or determining the value of minerals extracted can be further complicated by royalty systems that allow the mine operator to deduct costs associated with, refining, or smelting. Because of these complexities, a mine producing multiple minerals from the same ore body that are subject to different types of royalties, may need to use different methods for recording production volumes or determining market value at different stages in the mineral production process.

Environmental and Social Impacts

According to the EI Source Book, when compared with oil, mining operations generally have a larger footprint and thus have greater potential to cause adverse social and environmental impacts. A well designed system of environmental and social impact mitigation and monitoring involves early consultation and participatory monitoring practices at the local community level.

Similar to oil and gas, two common monitoring tools are environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) and environmental and social management plans (ESMPs). For ESIAs, companies analyze short- and long-term impacts through all stages of the project, and identify potential mitigation measures and monitoring methods. ESMPs are based on the ESIA, but provide more detail on how the company will manage impacts and comply with the conditions required as part of the project approval process.

See EI Value Chain Step 7: Implementing Sustainable Policies: Key Considerations for Mining for more information on mitigating environmental and social impacts.

Key guidance and further information

The following resources provide additional information on monitoring of operations for resource extraction.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI has guidance specific to companies’ social expenditures (Requirement 6.1), quasi-fiscal expenditures (Requirement 6.2) and economic contribution (Requirement 6.3).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI has guidance specific to companies’ social expenditures (Requirement 6.1), quasi-fiscal expenditures (Requirement 6.2) and economic contribution (Requirement 6.3).

IFC: The International Finance Corporation– member of the World Bank Group— has developed performance standards which define its clients’ responsibilities for managing their environmental and social risk. Topics include risk management, labor, resource efficiency, community, land resettlement, biodiversity, indigenous peoples, and cultural heritage.

IFC: The International Finance Corporation– member of the World Bank Group— has developed performance standards which define its clients’ responsibilities for managing their environmental and social risk. Topics include risk management, labor, resource efficiency, community, land resettlement, biodiversity, indigenous peoples, and cultural heritage.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. Sustainable Development provides additional information specific to extractive industries, including challenges, reform priorities, environmental and social impacts.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. Sustainable Development provides additional information specific to extractive industries, including challenges, reform priorities, environmental and social impacts.

World Bank: The World Bank has a paper titled “Extractive Industries Value Chain: A Comprehensive Integrated Approach to Developing Extractive Industries,” which addresses regulating and monitoring of operations in Link 2.

World Bank: The World Bank has a paper titled “Extractive Industries Value Chain: A Comprehensive Integrated Approach to Developing Extractive Industries,” which addresses regulating and monitoring of operations in Link 2.

ISO: The International Organization for Standardization is an independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 164 national standards bodies. It has standards for managing sustainable development, environmental impacts, and anti-corruption practices.

ISO: The International Organization for Standardization is an independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 164 national standards bodies. It has standards for managing sustainable development, environmental impacts, and anti-corruption practices.

WGEA: INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) developed guidance for auditing the environmental and other impacts of mining operations in 2010.

WGEA: INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) developed guidance for auditing the environmental and other impacts of mining operations in 2010.

Key audit considerations

According to AFROSAI-E, auditors provide oversight of government agencies and supervisory bodies, to ensure that the laws and agreements regulating the exploration, development and production of oil and gas are adhered to. Additionally, according to the Natural Resource Governance Institute, it is important for government agencies to monitor operations through the full project life cycle. Specifically, auditors should assess whether:

Figure: Monitoring of Operations: Key Audit Considerations

PIC

Figure sources: Summary of issues raised in AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries, the Natural Resource Governance Institute, and the World Bank’s EI Source Book

5. Collection of Revenue

The ability of a government to efficiently collect taxes, royalties, and other revenues depends on the choice of fiscal regime and fiscal instruments, and in part on the administrative and audit capacity of the relevant institutions.

According to the EI Sourcebook, given the very large amounts of money typically involved in oil, gas, and mining, and the transformative potential they have, it is critical to get the fiscal administration right. A well-designed but poorly drafted or implemented fiscal regime may fall far short of its tax-raising potential. The nonrenewable character of the extractive resources underlines the importance of sound fiscal administration.

Consequently, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative requires a comprehensive reconciliation of company payments and government revenues from the extractive industries. Understanding company payments and government revenues can inform public debate about the governance of the extractive industries.

Key considerations for oil, gas, and mining

According to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, governments may collect many different types of revenue from extractive industries:

- Taxes, or the value assessed based on profit from oil, gas or minerals

- Royalties, or the value assessed based on the sale of a volume of oil, gas or minerals

- Host Governments Production Entitlement

- State Owned Company Production Entitlement

- Dividends

- Bonuses, such as signature, discovery and production bonuses

- License fees, rental fees, entry fees and other considerations for license and/or concessions

- Any other significant payments and material benefit to government.

The oil and gas and mining industries are a complex, often heavily regulated sector. Auditors who intend to audit revenues from the extraction of minerals may need access to specialized knowledge and expertise to conduct their audit. Depending on the audit focus, a team may need the help of a tax or data-mining expert, an IT specialist, a lawyer, or an engineer, according to the Canadian Audit and Accountability Foundation

Figure: Strip mining operation

PIC

Figure source: GAO.

Key guidance and further information

The following resources provide additional information on the process for collection of revenue.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Revenue Collection (Requirement 4) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the collection of revenue.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI’s Revenue Collection (Requirement 4) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the collection of revenue.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a number of tax policy and revenue collection reports available on its website.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a number of tax policy and revenue collection reports available on its website.

IMF: The International Monetary Fund has a manual called the Fiscal Analysis of Resource Industries: (FARI Methodology) that introduces key concepts and methods for IMF’s fiscal analysis of resource industries (FARI) framework. The FARI framework is an analytical tool for economic and financial analysis at the project level.

IMF: The International Monetary Fund has a manual called the Fiscal Analysis of Resource Industries: (FARI Methodology) that introduces key concepts and methods for IMF’s fiscal analysis of resource industries (FARI) framework. The FARI framework is an analytical tool for economic and financial analysis at the project level.

World Bank: The World Bank published a guidance document, “The Extractive Industries Sector, Essentials for Economists, Public Finance Professionals, and Policy makers,” provides an overview of issues core to EI economics and critical fiscal challenges typically associated with large revenue flows from the EI sector, among other topics. Additionally, the World Bank’s “How to Improve Mining and Tax Administration and Collection Frameworks” provides an approach to help government ministries analyze and address challenges in mining taxation.

World Bank: The World Bank published a guidance document, “The Extractive Industries Sector, Essentials for Economists, Public Finance Professionals, and Policy makers,” provides an overview of issues core to EI economics and critical fiscal challenges typically associated with large revenue flows from the EI sector, among other topics. Additionally, the World Bank’s “How to Improve Mining and Tax Administration and Collection Frameworks” provides an approach to help government ministries analyze and address challenges in mining taxation.

Ernst and Young: Ernst and Young publishes a “Global Oil and Gas Guide,” which summarizes oil and gas tax regimes around the world.

Ernst and Young: Ernst and Young publishes a “Global Oil and Gas Guide,” which summarizes oil and gas tax regimes around the world.

CAAF: The Canadian Audit and Accountability Foundation (CAAF) is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to enhancing public sector performance audit, oversight, and accountability. It published the “Practice Guide to Auditing Mining Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation,” and Practice Guide to Auditing Oil and Gas Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation, which provide information to help performance auditors plan, conduct, and report the results of EI sector audits.

CAAF: The Canadian Audit and Accountability Foundation (CAAF) is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to enhancing public sector performance audit, oversight, and accountability. It published the “Practice Guide to Auditing Mining Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation,” and Practice Guide to Auditing Oil and Gas Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation, which provide information to help performance auditors plan, conduct, and report the results of EI sector audits.

PIC

Key audit considerations

According to the World Bank, the legal basis for the ownership of hydrocarbon and mineral resources and their exploration, development, and production is established in the constitution in many countries. Normally, a sector law (hydrocarbon and/or mining law), which is formulated at the parliamentary level, sets out the principles of law. Provisions that do not affect principles of law, or that may need periodic adjustments (such as technical requirements, administrative procedures, and administrative fees), are set in regulations.

Furthermore, the World Bank states that to ensure completeness of revenue collected it is essential to collect and verify data on the volumes produced, consumed, and exported and on the prices actually realized by the seller. Regular assessments help ensure that the realized prices of minerals and hydrocarbons sold from each project properly reflect market conditions and quality differentials at the time of the transaction.

Once the decision to audit the revenues from the extraction of minerals (and related questions) has been made, guidance from the Canadian Audit and Accountability Foundation recommends that the audit team start conducting research and interviewing officials to acquire (or further develop) a sound knowledge of the business and an understanding of the risks facing the organizations being audited. To develop their plan for auditing revenues, auditors may want to consider the following:

Figure: Collection of Revenue: Key Audit Considerations

PIC

Figure sources: Summary of issues discussed in Practice Guide to Auditing Mining Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation by the Canadian Audit and Accountability Foundation.

6. Revenue Management

The extraction of oil and gas has a potential of generating massive revenues. Once EI revenues have been generated and collected, a government must decide on their management and allocation, according to the EI Source Book.

A failure to manage properly the wealth arising from oil, gas, and mining operations can lead to poor growth outcomes and a misallocation of resources, including the promotion of social and economic inequalities, the funding of corrupt practices, and the generation of intra-state, or even inter‐state, conflicts.

Options include spending or saving with decisions required on appropriate channels or mechanisms for each. Sharing of resource revenues among levels of government and regions is increasingly common and Requires careful balancing of pros and cons.

Key considerations for oil, gas, and mining

When considering management of revenue from oil and gas, and mining activities, it is important to keep in mind the challenges and goals.

Challenges

According to the EI Source Book, there are four main challenges in managing EI revenues:

Figure: Revenue Management Challenges

PIC

Figure source: Summary of issues in the World Bank’s EI Source Book.

Goals

Although there are many challenges, governments can make decisions to use their natural resource revenues in a manner that has long-term positive social and economic impact on the country. According to the Natural Resource Governance Institute, there are 6 revenue management goals for policymakers to consider:

Table: Revenue Management Goals

PIC

Table source: Summary of issues in NRGI’s March 2015 Reader “Revenue Management and Distribution – Addressing the Special Challenges of Resource Revenues to Generate Lasting Benefits.”

Key guidance and further information

The following resources provide additional information on the process for revenue management.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas, and mineral resources. EITI’s Revenue Allocation (Requirement 5) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the allocation of revenue.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas, and mineral resources. EITI’s Revenue Allocation (Requirement 5) provides additional information on EITI standards related to the allocation of revenue.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a number of publications addressing revenue management.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals and has a number of publications addressing revenue management.

IMF: The International Monetary Fund’s Administering Fiscal Regimes for Extractive Industries: A Handbook focuses on effectively administering revenues from extractive industries. It offers guidelines to establish a robust legal framework, organization, procedures and capacity for administering revenue from extractive industries in developing and emerging economies.

IMF: The International Monetary Fund’s Administering Fiscal Regimes for Extractive Industries: A Handbook focuses on effectively administering revenues from extractive industries. It offers guidelines to establish a robust legal framework, organization, procedures and capacity for administering revenue from extractive industries in developing and emerging economies.

IIED: The International Institute for Environment and Development is a policy and action research organization that promotes sustainable development. Its paper Meaningful community engagement in the extractive industries: Stakeholder perspectives and research priorities explores what ‘meaningful community engagement’ means in the context of extractive industries, and the challenges faced by companies, governments and civil society organizations in ensuring that that community engagement leads to sustainable development outcomes.

IIED: The International Institute for Environment and Development is a policy and action research organization that promotes sustainable development. Its paper Meaningful community engagement in the extractive industries: Stakeholder perspectives and research priorities explores what ‘meaningful community engagement’ means in the context of extractive industries, and the challenges faced by companies, governments and civil society organizations in ensuring that that community engagement leads to sustainable development outcomes.

World Bank: The World Bank’s Rents to riches? The political economy of natural resource-led development provides an analytical framework for assessing a country’s political economy and institutional environment as it relates to natural resource management across the value chain.

World Bank: The World Bank’s Rents to riches? The political economy of natural resource-led development provides an analytical framework for assessing a country’s political economy and institutional environment as it relates to natural resource management across the value chain.

United Nations: The United Nations’ report on Extractive industries and indigenous peoples discusses international human rights standards for indigenous peoples in the context of extractive industries.

United Nations: The United Nations’ report on Extractive industries and indigenous peoples discusses international human rights standards for indigenous peoples in the context of extractive industries.

Key audit considerations

Oil and Gas:

AFROSAI-E has identified several high level considerations for revenue derived from petroleum. It suggests the auditor should consider whether:

Table: Revenue Management: Key Audit Considerations for Oil and Gas

PIC

Table source: Summary of issues in AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries.

Mining

The Canadian Audit & Accountability Foundation has similarly identified several high level considerations when auditing revenue derived from mining. It suggests the auditor should consider:

Table: Revenue Management: Key Audit Considerations for Mining

Table source: Summary of issues in the Canadian Audit & Accountability Foundation’s Practice Guide to Auditing Mining Revenues and Financial Assurances for Site Remediation.

7. Implementing Sustainable Policies

According to the United Nations’ World Commission on Environment and Development, sustainable development can be defined as development that meets the needs of present generations without compromising the need and the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainable development calls for an integrated approach to managing benefits and impacts in three distinct areas: economic, social, and the environment.

Figure: Implementing Sustainable Policies for Economic, Social, and Environmental Costs and Benefits

PIC

Figure source: Summary of issues in INTOSAI, Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining, 2010.

Key considerations for oil and gas

According to the EI Source Book, two key challenges for sustainable development are: identifying and implementing policies to ensure that EI sector investments lead to positive and sustainable impacts on growth and development and developing policies that minimize, manage, and mitigate the environmental and social costs and/or risks that accompany a decision to develop oil and gas resources.

Figure: Implementing Sustainable Policies for Oil and Gas

PIC

Table source: Summarized from the World Bank’s EI Source Book.

Key considerations for mining

According to INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, the purpose of a sustainable development framework for mining is to help ensure the minerals sector as a whole contributes to human welfare and well-being today without reducing the potential for future generations to do the same.

Table: Implementing Sustainable Policies for Mining

Table source: Summarized from INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions, 2010.

Key guidance and further information

The following resources provide additional information on a sustainable development framework for extractive industries.

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI has guidance specific to companies’ social expenditures (Requirement 6.1), quasi-fiscal expenditures (Requirement 6.2) and economic contribution (Requirement 6.3).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. EITI has guidance specific to companies’ social expenditures (Requirement 6.1), quasi-fiscal expenditures (Requirement 6.2) and economic contribution (Requirement 6.3).

IFC: The International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a member of the World Bank Group— has developed performance standards designed to help private companies operating in developing countries adopt socially and environmentally sustainable practices. Topics include risk management, labor, resource efficiency, community development, land resettlement, biodiversity, indigenous peoples, and cultural heritage.

IFC: The International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a member of the World Bank Group— has developed performance standards designed to help private companies operating in developing countries adopt socially and environmentally sustainable practices. Topics include risk management, labor, resource efficiency, community development, land resettlement, biodiversity, indigenous peoples, and cultural heritage.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. Sustainable Development provides additional information specific to extractive industries, including challenges, environmental and social impacts and relevant differences across EI sectors.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. Sustainable Development provides additional information specific to extractive industries, including challenges, environmental and social impacts and relevant differences across EI sectors.

ISO: The International Organization for Standardization is an independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 164 national standards bodies. It has standards for managing sustainable development, environmental impacts, and anti-corruption practices.

ISO: The International Organization for Standardization is an independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 164 national standards bodies. It has standards for managing sustainable development, environmental impacts, and anti-corruption practices.

Business and Human Rights Resource Center: The Business and Human Rights Resource Center is an independent, nongovernmental organization that tracks the human rights policy and performance of over 9,000 companies in over 180 countries, making information publicly available.

Business and Human Rights Resource Center: The Business and Human Rights Resource Center is an independent, nongovernmental organization that tracks the human rights policy and performance of over 9,000 companies in over 180 countries, making information publicly available.

WGEA: INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) developed guidance for auditing the environmental and other impacts of mining operations in 2010.

WGEA: INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) developed guidance for auditing the environmental and other impacts of mining operations in 2010.

Key audit considerations

From an SAI perspective, it is important to understand how social and environmental impacts are assessed, how the social and economic benefits of extraction are shared between the public and private sectors, and does the public sector have sufficient capacity to fulfill their responsibilities. Below are some of the key questions that SAIs could consider when assessing sustainable development policies.

Figure: Implementing Sustainable Policies for Mining

PIC

Figure sources: Summarized from the World Bank’s EI Source Book and AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries

Key Considerations When Auditing EI

Selecting and determining the scope of EI audits can be a challenge for SAIs. There are many ways of examining EI activities, depending on the type of extractive industry, the stage of a resource’s development, and the government’s relationship to EI within your country, among other factors. These pages provide information to help guide the audit scoping process for auditors who are new to EI, through four key steps, identified by INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing:

Figure: Four Key Steps for Scoping EI Audits

Figure source: Summarized from INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions, 2010

Identify extractive industries and related effects

As a first step to developing an audit approach, it is important to understand the scope of extractive industries within the country. For example, SAIs should determine which minerals are mined, the geographic extent of mining activities, the type of mining performed (e.g., artisanal or commercial), and the extent to which mining contributes to the national economy. Additionally, it is important to consider any short- and long-term economic, environmental, and societal effects related to the EI activity. There are several resources available to help auditors determine which extractive industries may be operating in their country:

![]() EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI and provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g. gas, oil, gold).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI and provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g. gas, oil, gold).

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals. Resource Projects is a clearinghouse of information collected by the Natural Resources Governance Institute on over 2,200 individual resource projects across the world. These data may include information on the EI company involved, the type of material extracted (e.g. oil), the status of the project, recent payments to governments, and production statistics.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals. Resource Projects is a clearinghouse of information collected by the Natural Resources Governance Institute on over 2,200 individual resource projects across the world. These data may include information on the EI company involved, the type of material extracted (e.g. oil), the status of the project, recent payments to governments, and production statistics.

OpenOil: OpenOil is an open source data repository of over three million compliance documents related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. Information includes EI concession agreements and contracts in about 70 countries.

OpenOil: OpenOil is an open source data repository of over three million compliance documents related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. Information includes EI concession agreements and contracts in about 70 countries.

Identify the government’s relationship to these activities

Governments play an important role in regulating extractive industries and its social, economic, and environmental effects. Specifically, governments have a variety of legal authority and tools that they use to oversee extractive industry activities. To develop an audit approach, it is important to understand the scope of the government’s authority and regulation of extractive industries within the country. There are several resources available to help auditors determine the government’s response to EI in their country:

![]() EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI, and most of these countries provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g., gas, oil, gold).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI, and most of these countries provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g., gas, oil, gold).

United Nations: The United Nations maintains a database of treaties and their participants, which can be searched to see which treaties your country has signed. There are a wide variety of international treaties, conventions and protocols that could be relevant to EI, such as the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

United Nations: The United Nations maintains a database of treaties and their participants, which can be searched to see which treaties your country has signed. There are a wide variety of international treaties, conventions and protocols that could be relevant to EI, such as the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contextual Framework has links to mining laws and regulations in 69 countries, and oil laws and regulations in 50 countries.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contextual Framework has links to mining laws and regulations in 69 countries, and oil laws and regulations in 50 countries.

Choose the appropriate audit type and topic

According to the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions, public-sector auditing is essential because it provides independent and objective assessments concerning the stewardship and performance of government policies, programs or operations. SAI roles in auditing EI vary by country and depend on the SAI’s legislative mandate.

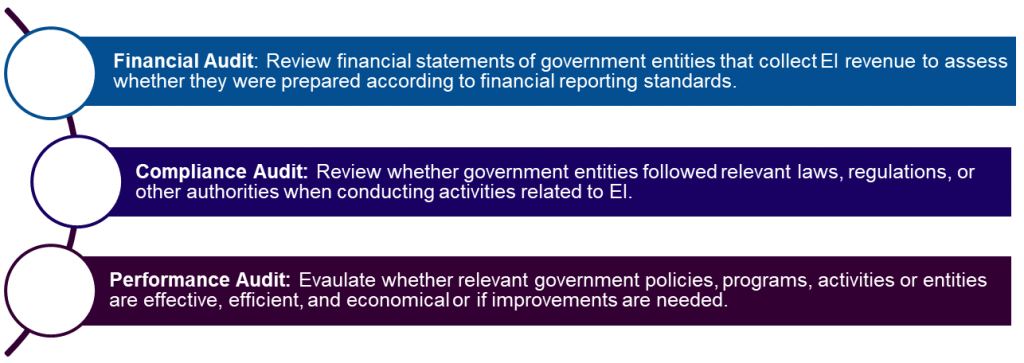

Generally, there are three types of audits: financial, compliance, and performance, as described in the figure to the right.

Figure: Three types of audits

Figure sources: Summarized from INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions, 2010

When choosing an audit topic, SAIs should assess how their work will be used and where it could have the greatest impact on improving the oversight of EI. Key questions to consider are:

- How will the audit be used and will it have an impact?

- Does the SAI have jurisdiction over the topic or entities involved and access to the necessary information?

- Is evidence available and are there suitable sources of criteria to compare efforts against?

Determine the audit approach

According to the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions, the overall audit approach is a central element of any audit. It determines the nature of the examination to be made and defines the necessary information and data and the audit procedures needed to obtain and analyze them.

The design process explores the variety of options available for collecting and analyzing information and can help auditors determine an audit approach that will best address the audit objective within available resources. A design matrix is one tool to help auditors identify the necessary information for each research question, as shown below.

Table: Using a design matrix to determine audit approach

PIC

Sources: Content summarized from the ISSAI Standard 300 and Appendix to ISSAI 5520.[Note: ISSAI Framework is migrating to IFPP]

Artisanal and small scale mining (ASM)

Artisanal and small scale mining (ASM) is a form of mineral extraction whereby individuals typically work independently with only small hand tools or basic machinery—and often outside of the formal legal framework and without regulatory oversight, to extract and sell minerals such as gold, silver, diamonds, and other precious gem stones. According to the World Bank’s Communities and Small Scale Mining (CASM) initiative, understanding the complex nature of ASM is critical to effectively implementing any measures to mitigate the negative and optimize the positive effects of these activities in the context of sustainable development.

ASM is a complex web of issues; spanning policy and regulation, environment, human health, culture and society, and economics. Governmental responses to ASM are typically intended to mitigate the potential harmful effects of ASM to human health and the environment, improve the lives of individuals and communities engaged in ASM and living in poverty, and prevent instances of violence and armed conflict associated with ASM.

Figure: How prevalent is ASM?

Figure source: Summarized from the International Institute for Environment and Development report Responding to Challenges of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining.

According to a report by the International Institute for Environment and Development, ASM is prevalent worldwide and can have a significant economic impact. For example, in the Central African Republic, two-thirds of its people are estimated to rely directly or indirectly on artisanal diamond mining and conservative estimates suggest it injects as much as $144.7 million into the economy. In Bolivia, mining makes up approximately 40 percent of current income from exports, 32 percent of which comes from ASM, with 85 percent of the mining sector’s total employment in small mining cooperatives and mines. Additionally, ASM is responsible for between 15 – 20 percent of global minerals and metals. Within this, the sector produces approximately 80 percent of all sapphires, 20 percent of all gold and up to 20 percent of diamonds.

Key Features of ASM

Figure source: Summarized from the International Institute for Environment and Development report Responding to Challenges of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining.

Challenges of ASM

Some of the inherent structural challenges facing artisanal mining include:

- Governance: Weak legislation, policies, and implementation and other government marginalization or repression of miners, including political exclusion from decision-making; lack of legal protection for land and resource rights; generally poverty-driven decision-making with focus on the short-term, may cause or prolong social/armed conflict.

- Societal Impacts: Reliance on mining in ASM communities due to vulnerability and marginalization based on culture or demographic group, with low barriers to entry into informal or illegal ASM with minimal health and social protections; associated uncontrolled migration of workers. Environmental hazards, such as mercury pollution, from ASM may have lasting effects in the area of mining and larger implications.

- Lack of Information: There is limited baseline or census data on ASM workers and communities. Further, because much of ASM activities occur outside of the legal framework, monitoring the supplies and revenue of ASM is particularly challenging and results in limited tax benefits for governments.

Key guidance and further information

OECD: The OECD issued guidance, “OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict-Affected and high Risk Areas,” as part of its efforts to further the responsible sourcing of minerals.

OECD: The OECD issued guidance, “OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict-Affected and high Risk Areas,” as part of its efforts to further the responsible sourcing of minerals.

World Bank: The World Bank sponsored the Communities and small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative. While the program has since ended, many of the documents may be found at http://www.artisanalmining.org. The World Bank also partnered with Pact to develop DELVE, a platform for artisanal and small-scale mining data that was piloted in 2017. More information about this initiative can be found here.

World Bank: The World Bank sponsored the Communities and small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative. While the program has since ended, many of the documents may be found at http://www.artisanalmining.org. The World Bank also partnered with Pact to develop DELVE, a platform for artisanal and small-scale mining data that was piloted in 2017. More information about this initiative can be found here.

IPIS: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute that provides information, analysis, and capacity enhancement to support those actors who want to realize a vision of durable peace, sustainable development and the fulfillment of human rights. IPIS has published papers on ASM.

IPIS: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute that provides information, analysis, and capacity enhancement to support those actors who want to realize a vision of durable peace, sustainable development and the fulfillment of human rights. IPIS has published papers on ASM.

Washington Post: The Washington Post published an extensive multi-media article on cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Washington Post: The Washington Post published an extensive multi-media article on cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.